Today is October 31, 2022: Happy Halloween! But it’s a day with even more symbolic value than costumes and candy. Perhaps more notable for some, it is the 14th anniversary of the advent of the world’s first successful cryptocurrency. On this day in 2008, a pseudonymous programmer by the name of Satoshi Nakamoto published a whitepaper entitled: “Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System.”

I’ve written around the topic of “crypto” (a catchall term for cryptocurrency, the blockchain, Web3, etc) a few times in the last year here on Getting A Grip, but haven’t written much about crypto itself: the technology, the history, its implications for the future, the innovations it enables, and why I’m so interested in it. I’m eager to share more on the topic and on related ideas like the metaverse, but feel it would be awkward/unfair to do that without laying out a bit of a foundation for you: my loyal and curious readers. So, I think it’s most logical to start at the beginning. No, not 2016: the start of my personal crypto journey. And not even back to 2008 with the start of Bitcoin. But all the way back to the time of pre-history, before there is even a solid written record. Back to the beginning of money itself.

What is Money?

We take for granted the concept of money: for most of my readers, the United States dollar, issued by the department of Treasury, signed by the Secretary of such, and marked as “legal tender for all debts, public and private,” is basically what we think of as money. Americans, and countries all over the world, to greater of lesser degrees can use the United States Dollar (USD) to pay their taxes, buy all manner of things, receive compensation for their work, to measure the value of various assets, or to save for the purchase of expensive things in the future.

The 1s and 0s stored on computer servers run by various banks that make up a ledger keeping track of your wealth denominated in United States dollars, British pounds sterling, or Japanese Yen, and readily redeemable for an equivalently valued paper version is about the best form of money we’ve come up with, which is why it’s used all over the world. But it’s far from perfect. Right now, for example, the USD is going through a significant devaluing process known as inflation that might be leading us into the first significant economic contraction in years. Money as it exists can also be stolen or manipulated, it is difficult to move it from place to place, and can be expensive to convert from one form to another.

But money doesn’t have to function the way it currently does, and in fact, this is just the latest version in a long iterative process going back thousands of years.

I think of money as a technology. And like all technologies, its invention arose out of necessity, and it is continually developing along with other technologies and social trends and desires. Specifically, money is a tool that serves its users to facilitate exchange: trade. Money enables trade between friends, among members of a community, or between nation states and multinational corporations. And like all technologies, new demands - for efficiency, speed, complexity - have yielded new features. Humans progressed from needing simple solutions to trade for their needs among members of their own tribe to needing an agreed upon standard that would enable reliable engagement with outsiders.

A (Very) Brief History of Money, Debt, and Banking

Ancient Commerce

Records exist going back as far as 9,000 BC with both livestock and crops serving as agreed upon means of exchange for all types of transactions in disconnected places around the world. Before the written record of trade its believed that individuals would engaged in a direct barter process, haggling to find agreement upon the value of the offerings. This significantly limited the number of trading partners an individual could have and generally restricted commerce to those within a discrete society or community.

Later, around 3,000 BC, with the invention and spread of writing, clay tablets were inscribed and transported to track and communicate the value of accounts. Specifically, these were used to settle debts, and the tablets would be retained by the lender, describing an amount to be repaid at a specific time, ie “the borrow agrees to repay the lender 500 bushels of grain at harvest time.”

Writing led to the advent of banking. In Babylonia, temples and palaces provided safe places for the storage of valuables, beginning with deposits of grain, and subsequently including cattle, agricultural tools, and precious metals.

Government Coinage

A fundamental change in the representation of value occurred around 2250 BC when the rulers of Cappadocia (a region of ancient Turkey) began stamping ingots (blocks) of silver, vouching for their purity and weight, leading to their acceptance as currency. The ingots were carried by traders and circulated throughout the Near East, freeing exchange from the constraints of physical agricultural commodities.

Things progress quickly from there with further developments in mathematics, law, and precious metal manipulation. Hammurabi encoded a slate of banking laws around 1750 BC including the advancement of capital and the charging of interest. Around 680 BC governments began issuing coins to facilitate commerce in the kingdom of Lydia. Athens issued two types of coins, experimenting with different materials, and found that lower valued pure bronze coins made for much better circulating money than they more expensive silver plated ones that citizens hoarded. During the reign of Caesar Augustus, around the time of Christ, the entire Roman monetary system was reformed and several coinage values were issued along with the creation of three important taxes: a general sales tax, a land tax, and a poll tax.

Paper Money and the “New World”

Paper money emerged in China in 910 to spare merchants the weight of carrying strings of coins long distances to engage in commerce. The paper money was essentially a form of receipt from deposit shops were other forms of money or goods were stored. Hundreds of years later, a similar development occurred in England where goldsmiths (who customarily owned great safes to store their gold) began to serve as bankers by letting their safes be used as deposits. They issued notes as receipts that also served as proof of ability to pay to others. Subsequently goldsmith receipts become banknotes and were fully accepted in lieu of coins or bullion for payment in England.

In the “New World” of America, currency was initially all over the place, with dozens of different forms of payment (from gold coins, tobacco, wampum, and corporately issued paper money) accepted as legal tender.

American Financial Primacy

Upon creation of the US Constitution in 1789, the government was given the power over the creation of money in the United States. The states were restricted from using or receiving anything other than silver or gold as legal tender. A few years later, upon passage of the US Coinage Act, the Dollar is adopted as the unit of account, and subdivided into 100 cents. After banking expansions and contractions, the California gold rush, the removal of legal status from foreign coins, the start of the Civil War, and the suspension of the ability to redeem bank notes for specie (gold or silver) upon request, the country moves to the issuance of US greenback dollars for use in all ordinary circumstances.

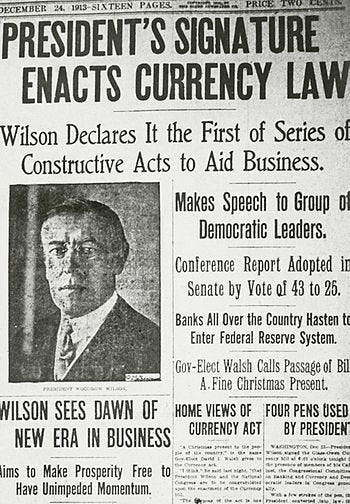

An era of tension over bimatalism persisted for decades until 1900 when the US officially abandoned silver and took up the Gold Standard, basing the monetary system on a fixed quantity of gold per a standard unit of account: the dollar. The Federal Reserve system is established 13 years later.

Over the next hundred or so years the US went through several financial booms and busts and stock market crashes, left the gold standard, attempted to resume the gold standard with the Bretton Woods Agreement, abandoned the Bretton Woods Agreement, and eventually abandoned the gold standard, leading to the current era of government run “fiat” money that gives central banks like the Federal Reserve greater control over the money supply.

Technological Evolution

The evolving real world needs of money led to subsequent innovations which define what money can be. The infinite transactions that can take place in a monetary society require that money is widely available. That same potentially infinite number of transactions requires that this money be durable, and that it doesn’t dissolve or dissipate when it changes hands. The need to accumulate money over time and take it with you, both to the site of a potential transaction or in the case of travel, requires that money be portable. And the need for any participant within a monetary system to be able to potentially transact with any other participant means that a money must be fungible, or easily interchanged with any other token of equal value.

These changing needs and cascading innovations have led to a money in the 21st century that is highly accessible, portable, and fungible. Money now largely exists beyond physical incarnation, as it’s mostly gone digital. As of the end of 2021 there were well over two trillion US dollars in circulation around the world. But, according to the Federal Reserve Board only $50 billion of that amount (2.5%) currently exists as physical bills or coins.

The digitization of money freed it from its physical limitations and enabled a universe of new possibilities. It allows both massive sums and infinitesimally small quantities to move around the world in previously unimaginable ways. Digitally represented money enables things like multi-decade international development projects, high frequency trading, and cash-like person-to-person experiences like Venmo.

Imperfection in the System

In the fallout of the 2008 Financial Crisis the world’s central banks acted with unprecedented force to increase the money supply in an attempt to solve financial liquidity issues and keep the world’s financial system from grinding to a complete halt. This action served to further distort the value of money from any generally agreed upon principle and, in conjunction with the lack of punishment for the speculation and irresponsible action that led to the crisis from the financial industry, many were left with devalued assets, without jobs, and frustrated at the seemingly illogical and unjust way money worked in the modern world.

The state of money is still a limited reality, filed with imperfections, and thus inviting innovation.

The Cypherpunks

At the dawn of the Internet age, before the concepts of email and websites had entered the lexicon of the average American, a privacy movement focused on individual liberties, was brewing in the San Francisco Bay area. The term Big Data had never yet been used, but a small group of computer programmers was seeing ahead to the potential dangers of surveillance that the Internet could bring. In September of 1992 they gathered at the Oakland home of cryptography enthusiast Erich Hughes to discuss what could be done about the future. Another cryptographer, with a more highly developed radical mindset, Tim May, a former physicist for the computing giant Intel, came prepared with a fully drafted essay he called the “Crypto-Anarchist Manifesto” that he’d written in 1988. From the essay:

A specter is haunting the modern world, the specter of crypto anarchy.

Computer technology is on the verge of providing the ability for individuals and groups to communicate and interact with each other in a totally anonymous manner. Two persons may exchange messages, conduct business, and negotiate electronic contracts without ever knowing the True Name, or legal identity, of the other. Interactions over networks will be untraceable, via extensive re-routing of encrypted packets and tamper-proof boxes which implement cryptographic protocols with nearly perfect assurance against any tampering. Reputations will be of central importance, far more important in dealings than even the credit ratings of today. These developments will alter completely the nature of government regulation, the ability to tax and control economic interactions, the ability to keep information secret, and will even alter the nature of trust and reputation.

[...]

Just as the technology of printing altered and reduced the power of medieval guilds and the social power structure, so too will cryptologic methods fundamentally alter the nature of corporations and of government interference in economic transactions. Combined with emerging information markets, crypto anarchy will create a liquid market for any and all material which can be put into words and pictures. And just as a seemingly minor invention like barbed wire made possible the fencing-off of vast ranches and farms, thus altering forever the concepts of land and property rights in the frontier West, so too will the seemingly minor discovery out of an arcane branch of mathematics come to be the wire clippers which dismantle the barbed wire around intellectual property.

Arise, you have nothing to lose but your barbed wire fences!

While perhaps a tad dramatic, May’s short essay perfectly encapsulated the great fears and great hopes placed in the liberating power of technology by this odd group. They truly believed that the individual would be liberated by the subversive power of the Internet and cryptography enabled private conversation and transaction.

The manifesto became the founding document of this group that called itself The Cypherpunks, in reference to cryptography and to the dystopian science fiction genre of CyberPunk that works like Snow Crash, Blade Runner, and Judge Dredd are drawn from. The Cypherpunks set themselves the task of creating tools to enable online anonymity, with the goal of enabling an open society, and shared their progress via email. They created an anonymous message remailer, which hid the identity of online correspondents. They started a project called BlackNet, intended to solicit secret government and corporate data to be made public a la the later WikiLeaks. Among their inventions was even an anonymous marketplace where no request was off limits.

March Toward a “Cryptocurrency”

Most importantly, the Cypherpunks were dedicated to the idea of creating a cryptocurrency that would give them the opportunity to transact anonymously and stay far beyond the reach of the most powerful entities of the day. A member by the name of Hal Finney was an early dabbler. Another member called Wei Dai, a cryptography expert and philosophy enthusiast, released a program called b-money that operated around anonymous peer-to-peer transactions and a centralized ledger. A third Cypherpunk, Adam Back, developed a program called “hashcash” in response to an early wave of Internet spam. Hashcash forced computers trying to reach him to do expensive computational work before giving them permission to send information.

The Cypherpunks made great strides toward anonymous digital money, but could never connect all of the pieces necessary to get it to work. Among other issues they repeatedly ran up against the double-spending problem. In a decentralized system, with no mutually trusted third party, users store identical copies of the transaction history. But transactions arrive to different servers at slightly different times. If a single token is spent by two different people, each respective server will take the first one it sees to be true, subsequently leading to a lack of consensus that could only be solved by a trusted third party, and thus a non functioning system. Despite their successive failures the Cypherpunks continued to attract enthusiasts, including an eventual participant who used a pseudonym: Satoshi Nakamoto.

Enter Bitcoin

On Halloween of 2008, Satoshi took a shot at correcting the imperfections of money and introduced something called Bitcoin to the world. Satoshi emailed a concise and well-polished technical paper to the Cypherpunk email list that included a brief introduction and technical details of the new cryptocurrency. From the whitepaper:

Abstract. A purely peer-to-peer version of electronic cash would allow online payments to be sent directly from one party to another without going through a financial institution. Digital signatures provide part of the solution, but the main benefits are lost if a trusted third party is still required to prevent double-spending. We propose a solution to the double-spending problem using a peer-to-peer network. The network timestamps transactions by hashing them into an ongoing chain of hash-based proof-of-work, forming a record that cannot be changed without redoing the proof-of-work. The longest chain not only serves as proof of the sequence of events witnessed, but proof that it came from the largest pool of CPU power. As long as a majority of CPU power is controlled by nodes that are not cooperating to attack the network, they'll generate the longest chain and outpace attackers. The network itself requires minimal structure. Messages are broadcast on a best effort basis, and nodes can leave and rejoin the network at will, accepting the longest proof-of-work chain as proof of what happened while they were gone.

Upon Satoshi’s publication of the Bitcoin whitepaper, the community of developers who’d gathered around these ideas instantly saw its value and got to work on further development and implementation, leading to the first “genesis block” of Bitcoin being mined and the network pushed live for the world to see in January of 2009.

Just Getting Started

In the fourteen years since the publication of the Bitcoin whitepaper, Bitcoin and the ever growing suite of other crypto projects, have not taken over the world. But crypto’s impact is growing. Crypto is now used all over the world for a wide variety of things from pure speculation to sophisticated financial transactions, and by millions of people as a vehicle for remittances - the regular transfer of money back to loved ones in native lands. Crypto is in the news every day now, and has been the subject at the top of the headlines in publications like TIME, and the New Yorker, while financially oriented outlets like Forbes and Bloomberg have founded dedicated imprints with journalists completely focused on the new form of money. And that’s not to mention the crypto specific media like Bitcoin Magazine, CoinDesk, CoinTelegraph, The Block, and Decrypt.

The world crypto “market capitalization” (the total dollar value of all money tied up in cryptocurrency and related projects) was as high as $1.75 TRILLION this summer, before the plunging market across all asset classes sent that number downward. But global participation is only showing signs of increasing with new user friendly applications launching every day and significant financial and business institutions making investments and forging partnerships in the space.

To say today that the creation of Bitcoin changed the course of history might be a bit premature, but I don’t believe that’s because crypto isn’t transformative enough to change the world for ever, and for the better…it’s still just getting started.

Author’s Note: The Journey Continues

I’ve attempted here to lay out a very general foundation to help you “Get a Grip” on crypto without getting too far into the weeds, or too philosophical. I plan to go further down the rabbithole with my writing in the future and explore the technical features that make crypto so special, the impact it’s already having on the structure of the internet, the increasingly complicated legislative and regulatory landscape, and hopefully many more things. In the meantime, I’ll link a couple of pieces in the past related to the subject.

Welcome to Digital Beaumont: Spindletop, Bitcoin, and the Creation of a Crypto Boomtown