Satoshi is Black

or The Pursuit of Property: Black Poverty and Prosperity Since 1619 and the Potential Promise of Crypto

There is an image of the prototypical cyrpto enthusiast in the collective imagination of America. He is the ‘Crypto Bro.’ The Crypto Bro is a young to middle aged white male who wears a hoodie or a fleece vest, and sits at his computer all day in Silicon Valley or New York. He uses his expert programming skills, or vast sums of money raked in from his finance job, to trade Bitcoin and NFTs all day. This person certainly exists. He is overrepresented on Twitter, where a lot of the conversation-setting discourse is taking place. He is writing the crypto think pieces in most of the legacy financial publications and even in the newer ones explicitly oriented around digital assets. He is on television. The Crypto Bro has set the narrative. But he is far from the only kind of person who has jumped into the game, or even gotten rich, in this new era of ‘magic Internet money.’

There’s not yet a wealth of longitudinal data quantifying the ins and outs of crypto ownership. This is somewhat inevitable given the pseudonymous (pseudo-anonymous) design of cryptocurrencies. But there are a number of high quality surveys and demographic studies that have sketched a rough, though helpful, picture: Black and Latino people are very excited about crypto, and have adopted digital assets into their portfolios at a significantly higher rate than other demographic groups.

Last year, results emerged from the first meaningful survey, conducted by the National Opinion Research Center at the University of Chicago, indicating that, of the Americans who held crypto, 44% of them were non-white. While this is less than a majority, it shows a significantly different proportion than more traditional investments, where likelihood of ownership is very tightly tied to race and ethnicity. The 2019 Survey of Consumer Finance, conducted by the Federal Reserve, indicated that only 2% of total stock value in the United States was owned by Black families, and only 1% was owned by Hispanic families. Data from that same study shows that 61% of white families own some stock, while the rate is at 34% for Black families and only 24% for Hispanic families.

Some of the most recent and comprehensive data, from another survey conducted by the Harris Poll organization colored the picture in with even more clarity. While only 11% of white Americans report owning any cryptocurrency, 17% of Hispanic Americans own digital assets, and nearly a quarter (23%) of all Black Americans hold some crypto.

There’s still a lot of information that researchers and interested parties like myself want to see, including about the relative wealth held in crypto by various demographic groups. As of now, you can only guess what these numbers might be. I surmise that the proportion of total wealth trends toward that of public equities, which are disproportionately owned by wealthier white investors, but I also assume it might not be as lopsided. Thus far, early adoption has been one of the most critical variables when considering crypto as an asset class. Trends have shown more conservative and substantial pockets of money have entered the space more recently, purchasing assets when the prices were already inflated, yielding a lower amount of any specific asset (Bitcoin, Ether, etc) per dollar invested. But they have entered the market in a big way, far outspending the capacity of earlier, and potentially more diverse, communities.

Clearly, Black people are intrigued by this new space, and are putting their money where their mouth is and getting involved. Why is that? In a world filled with easy access to more traditional equities through established companies and products like TD-Ameritrade, E-Trade, Charles Schwab, Fidelity, and Merrill Edge, and with fractional trading (which I argue has proliferated in direct response to the growth of crypto) platforms like Webull, Public, SoFi, and Robinhood that are as easy to download as any social media app...

Why are Black and brown people outpacing other groups in crypto participation?

I’ll address this question the way I do most complex issues...by looking backwards first. By getting a grip on the past I hope to more accurately understand the present, and to think more clearly about the future.

The Pursuit of Property - Black Poverty and Prosperity Since 1619

The story of Black wealth in America is not an uplifting one. It is not a tale filled with persistent progress building toward a happy present. The story of Black wealth in America is characterized by fits and starts, dotted with dazzling moments of brilliance and inspiration, and shaded by societal sabotage. But now, there’s a new light at the end of the tunnel. But it’s still far enough away that it’s difficult to tell whether it’s the light of freedom - open and welcoming - or the guiding light of a freight train.

The White Lion

Inequity and exploitation of Black people dates back to the earliest days of the land that would become the United States of America. In 1607, at the founding of Jamestown, the first British colony in the ‘New World,’ three ships: the Susan Constant, the Godspeed, and the Discovery, carrying a number of indentured servants were sailed across the ocean by the Virginia Company of London, to help tame the abundant and unruly land that far outstripped the capacity of the earliest settlers. Indentured servitude was hard. In exchange for the financing of their voyage across the Atlantic Ocean, these servants agreed to work four to seven years of hard toil. Most died before their time was up. But for those who made the journey, and survived the commitment, relative riches abound in the form of property. Twenty-five acres of Virginia land was promised, and rewarded to the workers, along with corn, arms, new clothing, and even a cow. Real startup capital that some were able to leverage to join the upper ranks of the burgeoning society, bestowing benefits upon generations of their descendants.

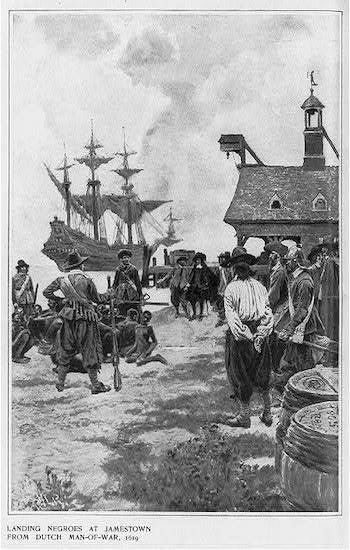

What I obviously left out of the description of these indentured servants is the fact that they were white. But just a dozen years after the founding of the first British colony, another ship, this one called the White Lion, landed at a place called Point Comfort, in today’s Hampton Roads, carrying passengers who had been kidnapped from Africa by Portuguese marauders, and stolen again, just off the coast by the White Lion. Several of the passengers were then sold in a historic transaction with the awaiting colonists who needed more workers to develop the land. John Rolfe - the first colonist to successfully cultivate the cash crop of tobacco, the husband of Pocahontas, and then the Secretary of the colony of Virginia - wrote a letter describing the journey and cargo of the White Lion to the Treasurer of the Virginia Company of London:

About the latter end of August, a Dutch man of Warr of the burden of a 160 tunnes arrived at Point-Comfort, the Comandors name Capt Jope, his Pilott for the West Indies one Mr Marmaduke an Englishman. They mett with the Treasurer in the West Indyes, and determined to hold consort shipp hetherward, but in their passage lost one the other. He brought not any thing but 20 and odd Negroes, which the Governor and Cape Marchant bought for victualls (whereof he was in greate need as he pretended) at the best and easyest rates they could.

This was 1619.

Those “20 and odd Negroes” were technically indentured servants. But unlike their white coworkers, they were not rewarded with property. They were mostly not rewarded even with freedom. And with the passage of a bevy of measures known collectively as the “slave laws,” those Africans, and the hundreds of thousands more who would follow, themselves became property.

In 1662, Virginia enacted a law of hereditary slavery, meaning that, unlike the limited tenure of indentured servitude, slavery was for life, and was a condition passed onto any child of an enslaved mother simply for being born. This was essential to the juggernaut American slavery would become. Between 1525 and 1866 less than 400,000 enslaved Africans were sent directly to North America. In 1790, upon the occasion of the first United States census, 697,624 slaves were counted. By the eighth census, conducted in 1860, the enslaved population had swelled to nearly four million.

Each colony passed laws further governing and restricting the lives of the enslaved. They combined into a network of regulations known as the ‘Slave Codes.’ Enslaved people were statutorily prevented from learning to read, from marrying, from meeting in private groups, and most importantly, for the purposes of our discussion today, they were prevented from owning any property. They could own nothing, will nothing, and inherit nothing, while their bodies could be, and were, sold, traded, and mortgaged by their owners.

The Lost Cause

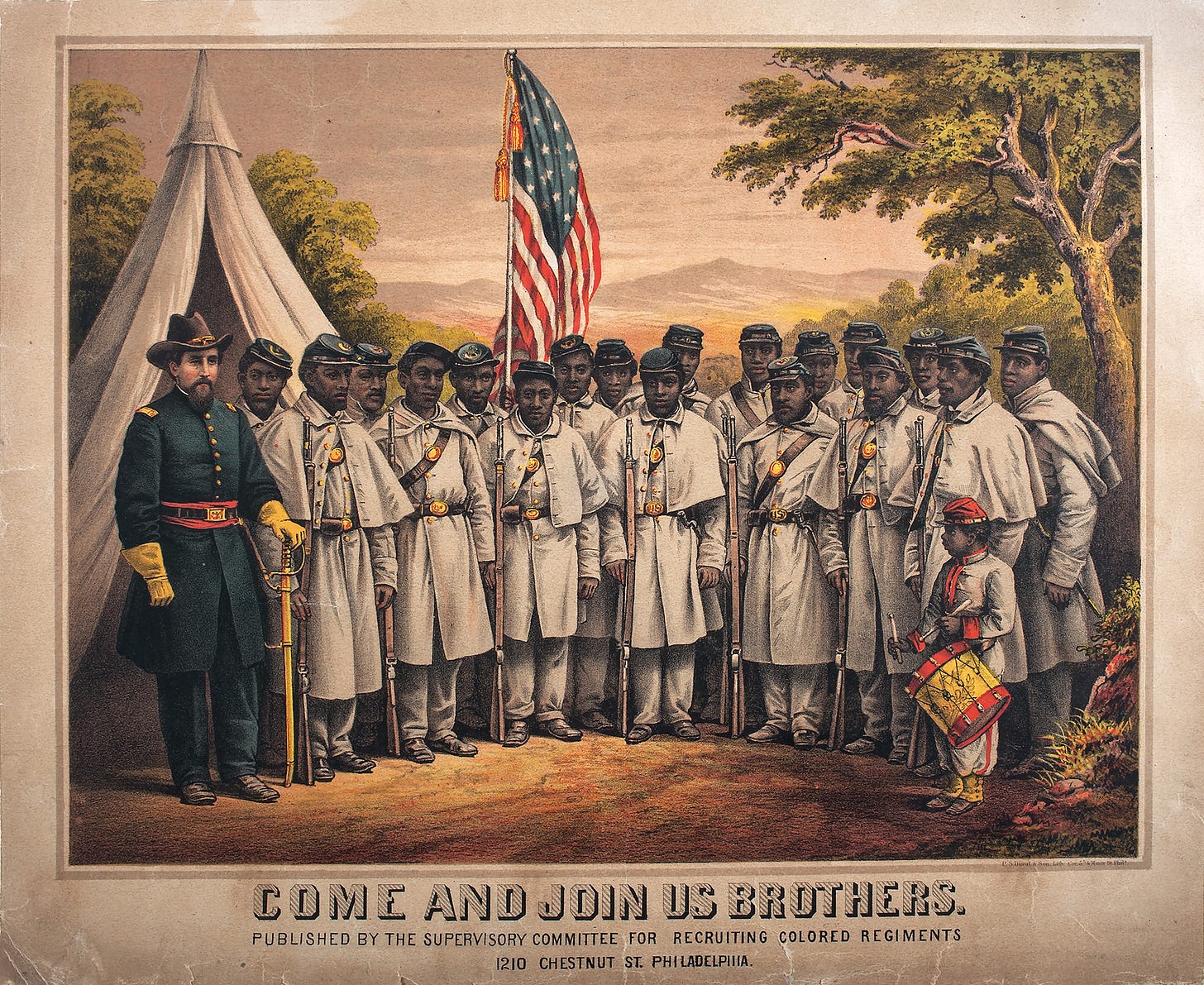

After centuries of chattel slavery in the United States, the young nation turned in on itself in 1861 and waged the conflict between the states. The Civil War was fought almost entirely over the issue of slavery and the central role the savage institution played in the economy and society of the Confederate states. Black people clearly had a vested interest in the outcome of the war, and put their lives on the line. Throughout the war, about 180,000 Black men served in the Union Army, making up 10% of the total fighting force. About half of them were “contraband” slaves who’d escaped from Confederate states to wage war against the only home they’d ever known. Initially, Black soldiers were paid $10/week, while their white counterparts were paid $13 with an additional clothing allowance. A law was passed in the last year of the war to give them equal pay. Forty thousand Black soldiers lost their lives during the war.

When the fighting ended, all wounded soldiers, including the Black ones, were promised pensions as compensation for their service. Many of the veterans, injured and often missing limbs, were unable to effectively return to their previous profession of farmer. The United States Bureau of Pensions, which had been created to serve veterans of the Revolutionary War, expanded dramatically in the wake of the Civil War. Eventually, disabled veterans, including those who were disabled due to age, their children and widows, all collected monthly allowances. By 1863 more than a million men were on the pension rolls, and pensions consisted of more than 40% of the federal government’s expenses. But this largess did not, in reality, fully extend to Black people. Their pension applications were rejected at a disproportionate rate by the federal government. Many had abandoned their slave names, and were rejected for that reason. They were less likely to be taken to field hospitals during the war and to have their injuries properly documented. And because Black people were almost universally illiterate and poor, they struggled to complete the applications or to travel to appeal their rejections to the pension boards.

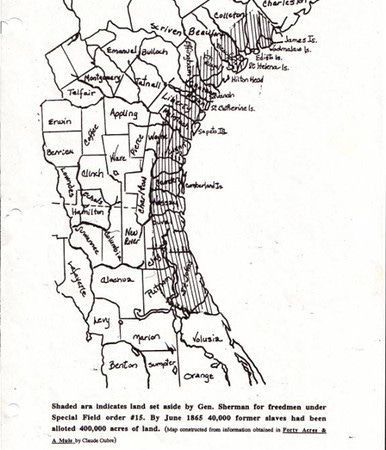

In the first month of 1865, after General William Tecumseh Sherman’s March to the Sea, cutting across the southern reaches of Confederate land and breaking the army’s ability to carry on, Sherman met with a contingent of Black ministers to evaluate what was to become of the enemy land. The spokesman of the small group, former slave, Reverend Garrison Frazier was asked what his people needed to make their way in a post-slavery world. He answered:

“The way we can best take care of ourselves is to have land, and turn it, and till it by our own labor — that is, by the labor of the woman and children and old men; and we can soon maintain ourselves and have something to spare.”

Four days after the meeting, Sherman issued Special Field Order No. 15. The order confiscated 400,000 acres of land - “a strip of coastline stretching from Charleston, South Carolina, to the St. John’s River in Florida, including Georgia’s Sea Islands and the mainland thirty miles in from the coast” - to be given to the newly freed slaves. Each family was to be given a plot of forty acres (provision of a mule was enumerated in a later order), and promised military protection from reprisal from bitter southerners. Black people were listened to, and responded to. They would be given the property they had labored over for centuries and allowed the opportunity to build wealth for the first time in the New World. Thousands of Black people flocked to the coastal region to claim what they were owed.

This moment of optimism would be short lived. After Lincoln’s assassination at Ford’s Theater, Andrew Johnson ascended to the Presidency. An apologist for the South, he immediately rescinded Special Field Order No. 15, and returned the land to the planters who’d previously owned it. Many Black people were penniless, propertyless, and forced into indentured servitude and sharecropping on the very land they had once worked as slaves.

Reconstruction and Jim Crow

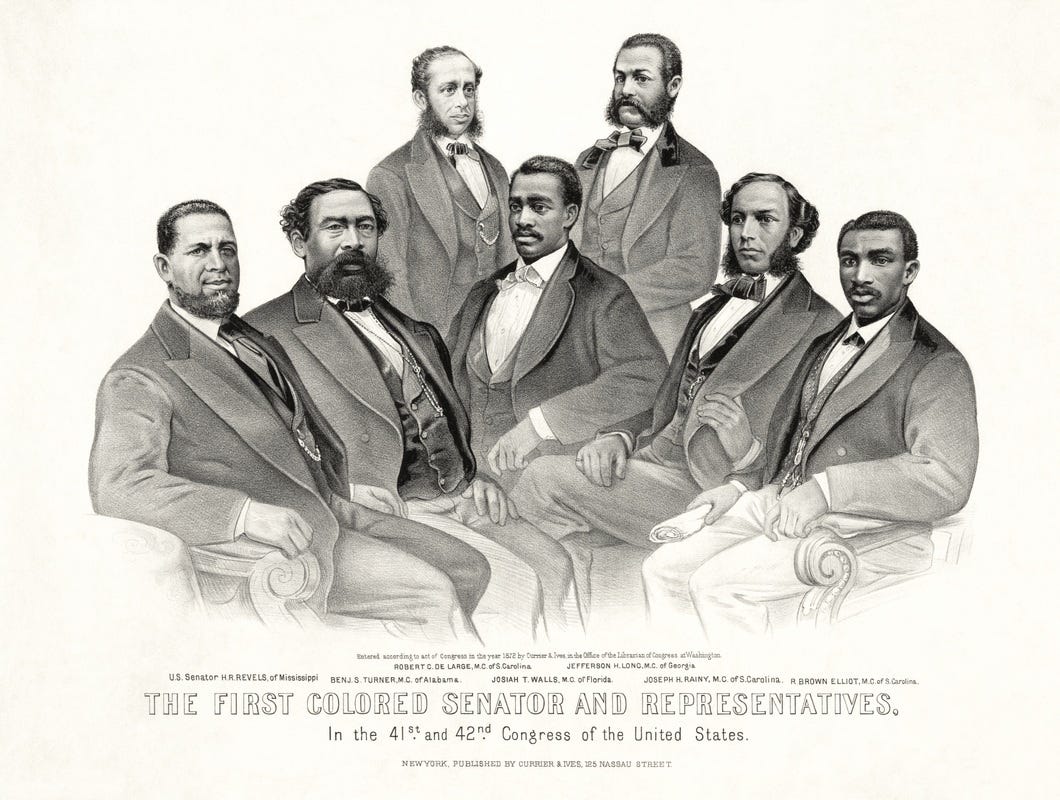

After the War, the reconstituted nation entered a brief period known as “Reconstruction.” By many measures, this was a bright light within a dark history for Black people. With the protection of the Thirteenth (abolishing slavery), Fourteenth (citizenship and equal protection), and Fifteenth (vote for Black men) Constitutional Amendments, and the Civil Rights Act of 1866, African Americans were allowed to vote, to actively participate in the political process, to acquire the land of former slave owners, to seek employment, and to use public accommodations.

With these protections in place Black people flourished. Black politicians rose to prominence, and Black owned, managed, and focused businesses were created across the South. The first Southern Black millionaire, Robert Reed Church, made a fortune buying and selling real estate. Black banks were created to help the community grow. Independent newspapers, like the South Carolina Leader, founded in 1865, emerged to tell the first rough draft of history from the Black perspective.

This era however would be short lived. By the mid 1870s a backlash was taking shape across the South. The overall Southern economy was in steep decline in the wake of war. Fear and racism spread and manifested in all out discrimination against Blacks that came to be known as Jim Crow. The term “Jim Crow” referred to a 19th century blackface minstrel character whose name was used as a pejorative epithet for Black people. Crow was lazy, foolish, loud, dumb, and obviously inferior to the status and bearing of white people in America.

Racist Democrats took office across the old Confederacy and installed laws of oppression to put Black people back into their place. Powerful people and regular folks alike employed brutal and cynical intimidation tactics to keep Blacks away from the political process. Economic scare tactics and physical and psychological terrorism including public lynchings proliferated. The federal government reaffirmed the discriminatory provisions put in place, which were enshrined in three particular sets of cases:

The Slaughter-House Cases (1873) - this series of three cases, which were consolidated into one issue, offered the first opinion from the Supreme Court on the 14th Amendment. The court chose to interpret the rights protected by the 14th Amendment very narrowly.

Civil Rights Cases (1883) - in this set of five cases that were consolidated into one issue, a majority of the court held the Civil Rights Act of 1875 unconstitutional. The majority argued that Congress lacked authority to regulate private affairs under the 14th Amendment and that the 13th Amendment only ended slavery.

Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) - this is the case which gave us the phrase "separate but equal" and upheld state racial segregation laws for public facilities.

In response to the closing of their brief window of a better life, Black people began to move across the country en masse in search of opportunity. During this Great Migration Black people established new communities in New York City, Los Angeles, Chicago, Detroit, and elsewhere, and again created some measure of prosperity for themselves. The NAACP was founded in 1909. The Harlem Renaissance took root and gave the world the words of Langston Hughes and Zora Neale Hurston, the sounds of Duke Ellington and Ella Fitzgerald, among many other beautiful things.

But where Black people and prosperity went, hatred and trouble would follow.

Red Summer

In late 1918 380,000 Black veterans began demobilizing from the First World War, and by 1919 200,000 had returned from Europe. Black servicemen were seen as inferior and many were not allowed to see combat, but two divisions, the 92nd and 93rd, did. The 396th Infantry Regiment of the 93rd division received particular renown for their courage and tenacity. They were known by several names, including The Harlem Hellfighters, The Black Rattlers, and the Men of Bronze, and gained national acclaim. Black veterans proudly wore their uniforms and assumed that their participation in the patriotic exercise of war would make their fellow countrymen see them as equals. In fact, their newfound pride was punished with a season of national violence and terrorism so profound it would come to be referred to as The Red Summer.

More than two dozen anti-Black riots sprang up in cities across the country. From Washington, DC to Chicago, to Houston, and Omaha, white citizens, many of them veterans home from war, attacked Black communities. They were met with substantial resistance from their fellow veterans, but were able to overwhelm resistance with superior numbers and arms. These larger riots killed scores of Black people at a time. And many more were lynched in one-off acts of hatred.

This is the country to which we Soldiers of Democracy return. This is the fatherland for which we fought! But it is our fatherland. It was right for us to fight. The faults of our country are our faults. Under similar circumstances, we would fight again. But by the God of Heaven, we are cowards and jackasses if now that that war is over, we do not marshal every ounce of our brain and brawn to fight a sterner, longer, more unbending battle against the forces of hell in our own land.

W.E.B. Du Bois, Returning Soldiers (May 1919)

Black Wall Street

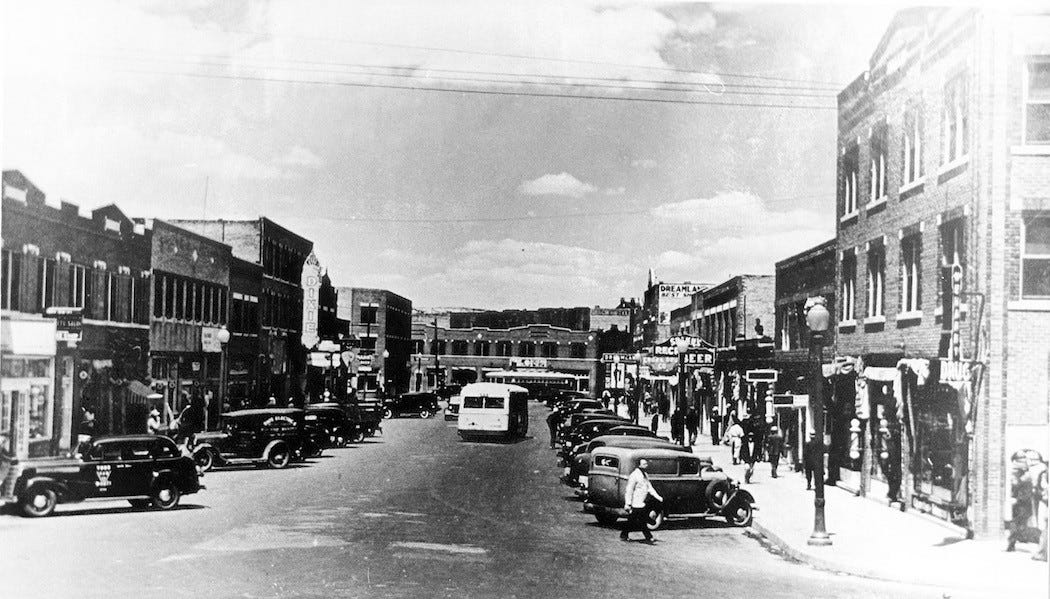

As a result of the Great Migration and demobilization from the Great War, one of the most successful of all the new pockets of Black success was a section of Tulsa, Oklahoma called Greenwood. Founded by optimistic Black entrepreneurs Stanford and Gurley - who bought large tracts of land north of the train tracks - Greenwood was known as Black Wall Street because of its astounding financial prosperity and economic development. The community of 10,000 residents was home to scores of powerful Black owned businesses. Black real estate agents, physicians, tailors, lawyers, photographers, insurance providers, grocery and drug stores, numerous restauranteurs, dry goods purveyors, bar owners, two newspapers, and a hospital all called Greenwood home.

On the morning of June 1, 1921 - barely a century ago - Greenwood was attacked. An unsubstantiated incident between a white person and Black person on an elevator two days prior set off a powder keg of tension and jealousy that had long been targeted at the thriving Black community.

At dawn an armed white mob - some of whom had been quickly deputized and armed by the police - marched into Greenwood. They shot and beat Black people, stole property, set fire to homes and businesses, and generally caused mayhem. Unfathomably, airplanes were even deployed as agents of chaos in the tragedy. They flew over and dropped bombs of nitroglycerin, turpentine, and dynamite upon the city, terrorizing its denizens. (The first episode of the hit HBO series, The Watchman, features a striking dramatization of this nearly unbelievable event).

The destruction from that one day of horror, now often referred to as the Tulsa Massacre, is incalculable. Estimates put the loss of life as high as 300, with hundreds more injured. Thirty-five blocks of residences and businesses were burned to the ground. Over a thousand homes were looted and destroyed. Thousands were left at least temporarily homeless. The most comprehensive estimates - including the loss of property, pervasive theft, and physical destruction put the total damage at around $200 million in 2022 value.

But the real damage done to the dream of Black American wealth is incalculable and deeply depressing. Black Wall Street was no more. Greenville did rebuild, and some of its citizens were successful once again, but many of them were not. They were forced to relocate and start over. Some of them had to rebuild from less than zero, as they were indicted with trumped up charges of inciting a riot. Charges which stuck with them until their death.

Red Lines

The development and growth of towns like Greenwood is part of a larger American economic story of prosperity during the “Roaring Twenties.” Capital flowed and productivity soared. That all came to a halt along with the collapse of the stock market. On October 28, 1929, the Dow Jones Industrial Average (a collection of companies that are seen as representative of the health and performance of the broader market) dropped thirteen percent. Then it dropped twelve more the next day. It lost half its value in the next two weeks, before dropping further. By the summer of 1932 the market had lost nearly ninety percent of its value.

The crash of the stock market didn’t harm many Black Americans directly, as they had very little equity ownership in publicly traded companies. But the economic turmoil that the crash precipitated, the Great Depression, weighed heavily on Black communities. Black workers were the first to be laid off from their jobs, and eventually experienced an unemployment rate two to three times worse than that of their white fellow citizens. The tight competition for resources around the country led to more strife and race based violence. Lynchings, which had decreased from the early days of Jim Crow, surged through the 1930s and wanton attacks on Black communities were common.

To address the Great Depression, President Roosevelt embarked upon a sweeping policy agenda called the New Deal. Programs were developed to create jobs, to preserve history, to commission art, and to build infrastructure. The demand for housing was particularly acute. There simply was not enough, and many American homes were being foreclosed upon by the banks. To address these issues, Congress passed the National Housing Act in 1934. Among other things, the legislation created the Federal Housing Administration (FHA), and endowed it with a mandate to insure mortgages made by private lenders for homes. The FHA took up this charge with zeal and led a transformation of the US housing market, making homes significantly more accessible and affordable for the average American. Unfortunately, this revolution was largely denied to Black people.

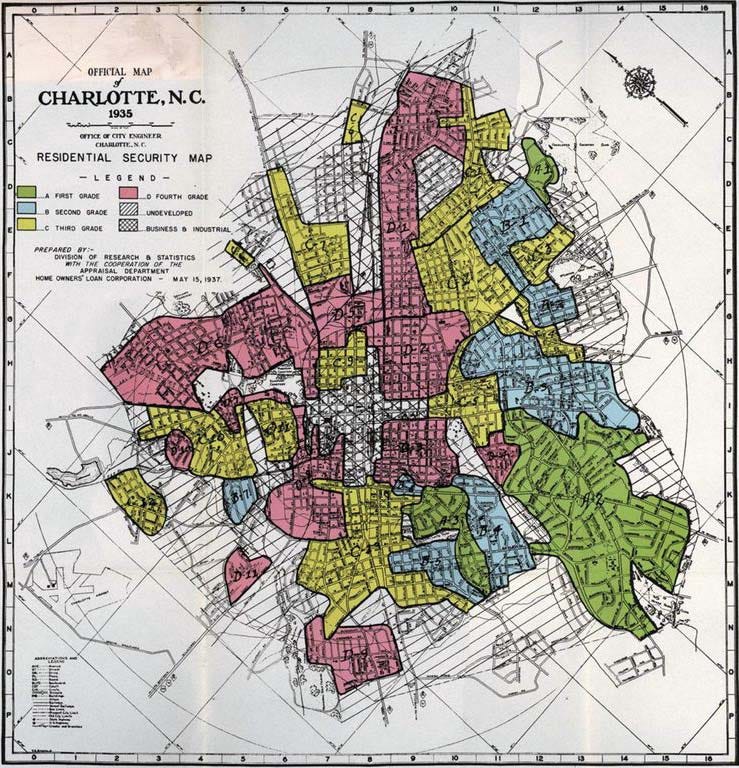

The FHA hired and disseminated an army of agents to appraise homes and neighborhoods around the country. They were given an Underwriting Manual and taught eight criteria with which to calculate appraisal values. They were able to lend more money for homes appraised at a higher valuation. Two of the most important of the eight aforementioned criteria were “Relative Economic Stability,” which made up 40% of the calculation and “Protection from Adverse Influences,” which made up another 20%. The appraisal guidelines also included a “whites only” standard for some neighborhoods, making segregation an official feature of the program. Color-coded maps created by the federal government ranked the loan worthiness of communities in hundreds of jurisdictions across the country. Black neighborhoods were marked in red, giving the practice its infamous name: “Redlining.” These practices and more led to the FHA’s insurance of Black homes as a proportion of only 2% of all federally insured home loans through 1959. When white Americans were given a helping hand by the government, Black Americans were pushed down ever further.

The Second World War

In 1942, as the United States prepared to enter the fray of the Second World War, the government took to the press and the airwaves to highlight the atrocities taking place at the hands of Adolph Hitler, and spoke profusely of the American ideals of democracy and human rights. Black people, with the Red Summer still fresh in their minds, and particularly in the minds of veteran parents with fighting age sons, listened carefully, and skeptically, to the rhetoric. Black leaders fought for guarantees from the government that enlistees would not be restricted from the various positions in the military, including prized combat roles, and that they would have full access to all rewards owed them in the wake of service. Full wartime mobilization also meant that there would be a large number of good paying government jobs created domestically to support the fight, and Black leaders didn’t want to be excluded from the opportunity to gain skills and build wealth. They called this overall effort, for great equality and access during the war, the “Double V” campaign. A campaign for victory at home, and victory overseas.

“In our fight for freedom, we wage a two-pronged attack against our enslavers at home and those abroad who would enslave us.” - Pittsburgh Courier

The Double V campaign yielded immediate positive results, but like so many of the potential game changing moments for Black wealth and equality in the country’s history, they would quickly be undercut. The Selective Service Act of 1940 allowed greater numbers of Black Americans to join the military, provided aviation training for Black officers, and allowed Black and white officers to train together. And in 1941 President Roosevelt issued Executive Order 8802, outlawing racial discrimination in the war industry. But the government body created to enforce this mandate, the Fair Employment Practices Committee (FEPC), was given no real regulatory authority and was met immediately with insurmountable resistance from southern governors. And within the military, Jim Crow remained the ruling practice at home and abroad. Troops were segregated and Black soldiers were mainly given important duties only when circumstance absolutely demanded it. Those who were asked to rise to the occasion - The Tuskegee Airmen, the 6888th Central Postal Battalion, the 92nd Infantry Division, and the 761st Tank Battalion - succeeded beyond all expectation. But the majority of Black units were relegated to essential, but underwhelming, support roles.

After American troops claimed victory in Europe and then in Asia, they returned home in droves. The nation demobilized and evolved, leading to an unprecedented period of economic growth powered by public and private investment, industrial conversion from the manufacture of war materiel to consumer products, increased education, and home ownership. But Black veterans, and the Black workers - men and women - who had filled critical roles on the home front, would be disproportionately left out of this post-war American boom.

The G.I. Bill

In 1944, President Roosevelt signed the Serviceman’s Readjustment Act, popularly known as the G.I. Bill, into law. The G.I. Bill promised to provide returning veterans with funds to further their education with college degrees, to deliver significant unemployment insurance if they couldn’t find a good job, and to offer low-cost mortgages, and low-interest loans. Its implementation created the unprecedented middle-class that has become the hallmark of American prosperity. Uncle Sam sent over two million veterans to college, and another five million to trade school, by covering the cost of attendance and helping veterans support their families while pursuing degrees. Millions more took advantage of the financial benefits to acquire businesses and farms and to build or buy homes. This dramatic increase in home ownership was the primary driver of individual wealth creation in the post-war era.

Though the G.I. Bill doesn’t include explicit provisions to exclude Black veterans, it was drafted to pass through a Congress that was dominated by Southern Jim Crow abiding Democrats, and delegated all administrative responsibility to the states. This intentional detail (a feature, not a bug) effected Black access to the full suite of benefits, but particularly hampered the pathway to home ownership that has become the backbone of prosperity in the United States. Title III of the legislation made veterans eligible for low-interest home loans with NO DOWN PAYMENT. The federal government guaranteed the loans, but the loan had to first be acquired in contract with a local bank. This meant in practice that Black veterans did not benefit from this provision. Banks then (as too often is still the case today) routinely denied loans to Black applicants.

Again, Black Americans were denied an incredible opportunity to amass property, specifically to own their own homes, by far the most important path to real wealth appreciation in this country. The era immediately following the war would not be the last time Black people were left out, negligently or intentionally, from opportunities to increase their economic lot. Black veterans continued to be excluded from benefits promised to them and delivered to the comrades. Black workers continued to be hired last and fired first from their jobs. Black communities were devastated by the War on Crime, uprooted by Urban Renewal, and continued to feel the weight of national economic downturns more heavily than their peers. Recessions in America yielded depressions for Black people.

The Financial Crisis

For over a century, a homeownership gap between 20 and 30 percentage points has existed between Black and white Americans. Today, over 70 percent of white Americans own their home, while that number hovers closer to 40 percent for Black people. Fewer Black people own their own homes because of less access to credit and lower amounts of family wealth. They have less wealth largely because they are less likely to own their own homes. A vicious cycle.

It was this particular weakness, the low rate of home ownership, that was preyed upon by unscrupulous lenders in the run up to the Financial Crisis of 2008.

Black home ownership rates in America peaked in 2004, years before the Financial Crisis burned the rest of country, because Black families were already losing their homes. Starting in the 1990s minority communities became targets for subprime mortgage lending. A “subprime” mortgage is a home loan given to an individual with a background that would typically characterize them as a less than ideal recipient ie, little or no credit, or a lower income. Subprime loans were pedaled as an innovation that gave communities that had typically been excluded from the housing market a chance to buy. Minorities, particularly Black people, were an obvious target. The catch with a subprime loan is that they often come with “subprime” features like very high interests rates that grow over time. Balloon mortgages, where a buyer pays low rates on a home for five or more years before having to pay the entire remainder of the loan at once, often forcing them to get another loan, were common. As were adjustable rate mortgages, that came with affordable low “teaser” interest rates initially, before jumping up to unsustainable levels after three, five, or seven years.

Though they led to an increased amount of foreclosures, particularly in Black and brown communities, these accessible loans were pushed by the housing industry and adored by Wall Street. National interest rates were low, and the housing market had been growing for years, leading some overly optimistic commentators in the early 2000s to believe that it would never crash. This “predictable” growth precipitated the proliferation of complex collateralized securities that exposed the entire economy to the potential impact of the bubbling housing market.

Banks were bundling home loans into packages that collected individual payments and paid investors lucrative high-yielding coupons. This process created an asset backed security where the underlying real estate served as collateral to secure the loans. Through a sophisticated layering process bankers combined subprime loans with highly secure loans to create a seemingly rock-solid investment. This gave subprime lenders a place to sell the debt obligations they’d collected from home owners, and encouraged them to market their subprime offerings even more aggressively.

The entire process of securitizing the housing market (which I have dramatically oversimplified here) was built on the shaky foundation of low interest rates, low lending standards, and predatory mortgages. But problems arose in time. Inflation crept in, which led to fears of rising interest rates and decreased consumer confidence. New home sales finally slowed, and home prices stopped edging skyward. When more and more people defaulted on their loans, the house of cards began to tumble. Credit dried up, the markets seized, and “smart money” fled to reliable investments. And in 2008, the everyman was left holding the bag.

The government bailed out the biggest banks, who’d played a critical role in engineering the crisis. Increased expenditure and decreased revenue during the crisis cost the government $2 trillion. A 2018 study found that, over a decade, the crisis probably cost each American $70,000 in lost income. And between 2007 and 2010, there were nearly 4 million foreclosures on American homes. Many of them were the homes, often the first owned home in generations, of Black and brown people. And as in previous crises, minorities were the first to be fired when times got tough, and were the last to be hired back when things returned to normal.

In the immediate fallout of the Financial Crisis, Black household net wealth plunged by over half on average. White household wealth fell by about 17 percent on average. And in the years since (but before Covid), most of the economy has completely recovered, with some pockets standing stronger than before. The Black community has still not caught up to the rates of home ownership and household wealth they had attained before the Financial Crisis and the ensuing Great Recession.

Enter Satoshi

And it was into this world that Satoshi Nakamoto and Bitcoin emerged.

On Halloween of 2008 a pseudonymous online figure calling itself Satoshi Nakamoto published a technical document introducing a new concept called Bitcoin: A Peer to Peer Electronic Cash System. While inconspicuous in its presentation this paper would yield a new digital currency and an ensuing explosion of technological innovation and excitement not seen since the dawn of the Internet. The document, now affectionately referred to by crypto fans the world over simply as ‘The Whitepaper,’ offered instructions to create a new kind of money that could exist beyond any financial institution or government, completely based on mathematics and computer code that would be left open for all to see.

The idea for something like Bitcoin had been tossed around in universities and on online forums for years, but no one had been able to successfully implement all of the technical steps necessary. Satoshi solved something called the ‘double-spend problem’ (the idea that a completely virtual money, or anything virtual, could be copied and re-spent or shared ad infinitum) with the creation of an entirely new concept called the blockchain. A blockchain is a growing record of data that encapsulates and timestamps all transactions occurring on a decentralized network of independent computers. When groups of data are timestamped onto the record, or ‘chain,’ an algorithm called a cryptographic hash is used to seal the data into a ‘block’. Each successive block of data is influenced by the previous block, giving the blockchain an immutable nature, since the altering of any block would disrupt or break the rest of the chain.

Bitcoin’s immutable, decentralized, and open source characteristics attracted a growing cohort of enthusiasts. First, a small group of folks in the know came to play and learn about the novel computer science experiment. Then people started trading bitcoin tokens for government-backed currency and created a market. It started slowly, but the longer the network stayed up, the more people began to have faith in the technology. Exchanges developed to enable people without the technical savvy to run the software on their own computers to get involved. New users found new uses - like sheltering their money from runaway inflation in unstable countries, sending remittances home quickly across borders, or transacting directly in a cash-like manner - and the price began to rise. The rising price drew more people to Bitcoin, which subsequently proved its technological soundness, and on and on, developing a flywheel of speculation and adoption that hasn’t let up since.

As with every technological innovation since the dawn of time, the new technology was quickly abused by those looking to make a quick buck off the trust and naivety of others. A substantial informational asymmetry between some bad actors and newcomers, and the understandable exuberance of many of those newcomers, left many vulnerable to exploitation, fraud, and risk. Countless scams promising that participants would strike it rich overnight have been run to various levels of success. Terrorists, thieves, and hackers have used the pseudonymous properties of Bitcoin and other tokens to subvert laws and move money surreptitiously. But this is a minority of the usage.

Freight Train or Freedom

Many Black people, who’ve had a long and torturous relationship with wealth and money can instantly feel the potential benefits of Bitcoin and the cyptoassets it’s inspired. No one can stop you from acquiring it. You can hold it yourself, on a personal piece of technology, or as a string of digits in your head, and neither the government, nor the controlling entities of society (big banks corporations, etc.) control it. It is this piece in particular, that I think makes crypto so appealing to those who’ve been left out and left behind by our nation.

Integral to each of the historical instances I detailed in this essay (small book?) is the complicity of the government and the financial system it has allowed to develop. Slavery was a state sanctioned enterprise, deeply intwined with all facets of American capitalism. Jim Crow was enshrined in law, at the state and federal level, and reinforced at every strata of society. The Federal Housing Administration deployed racist policies drafted in the halls of Congress, and local banks leaned on them to justify their refusal to give loans to Black families. “Too big to fail” financial institutions engineered sophisticated speculative products with predatory loans at their foundation, and the government bailed them out, not the suffering citizen, when things fell apart.

The crypto revolution is just beginning. And while I’m a believer in the transformative and democratizing potential of the technology, I’m fully aware that any given token - whether Bitcoin, or Ethereum, or any of the thousands that have followed in their footsteps - could spiral to a valuation of zero tomorrow. But even with that possibility firmly planted in my mind, the allure of financial sovereignty and the freedom to transact, to HODL, to sell, to gain or lose value as a result of my own decisions is too powerful to ignore.

If your people had a two hundred year history of being property, followed by a hundred and fifty more years of being denied the reasonable opportunity to amass property, and you spotted a light at the end of the tunnel...could you ignore it?

Expertly crafted.