In 1787 a British thinker by the name of Jeremy Bentham published a series of 21 letters in response to an advertisement he’d seen in the paper. The ad was regarding a House of Correction. Parliament was preparing to deport thousands of prisoners to Australia (they had been sending convicts to the colonies across the Atlantic, but that system ended with the American revolution) and was looking for some new prison designs. Bentham went to great length detailing a structure he thought might fit the bill. His design would allow a large number of subjects to be overseen by a minimum number of monitors. He called it the panopticon or Inspection House.

PAN-OPTI-CON, From the Greek: pan (all) opti (seeing). Bentham described it as such:

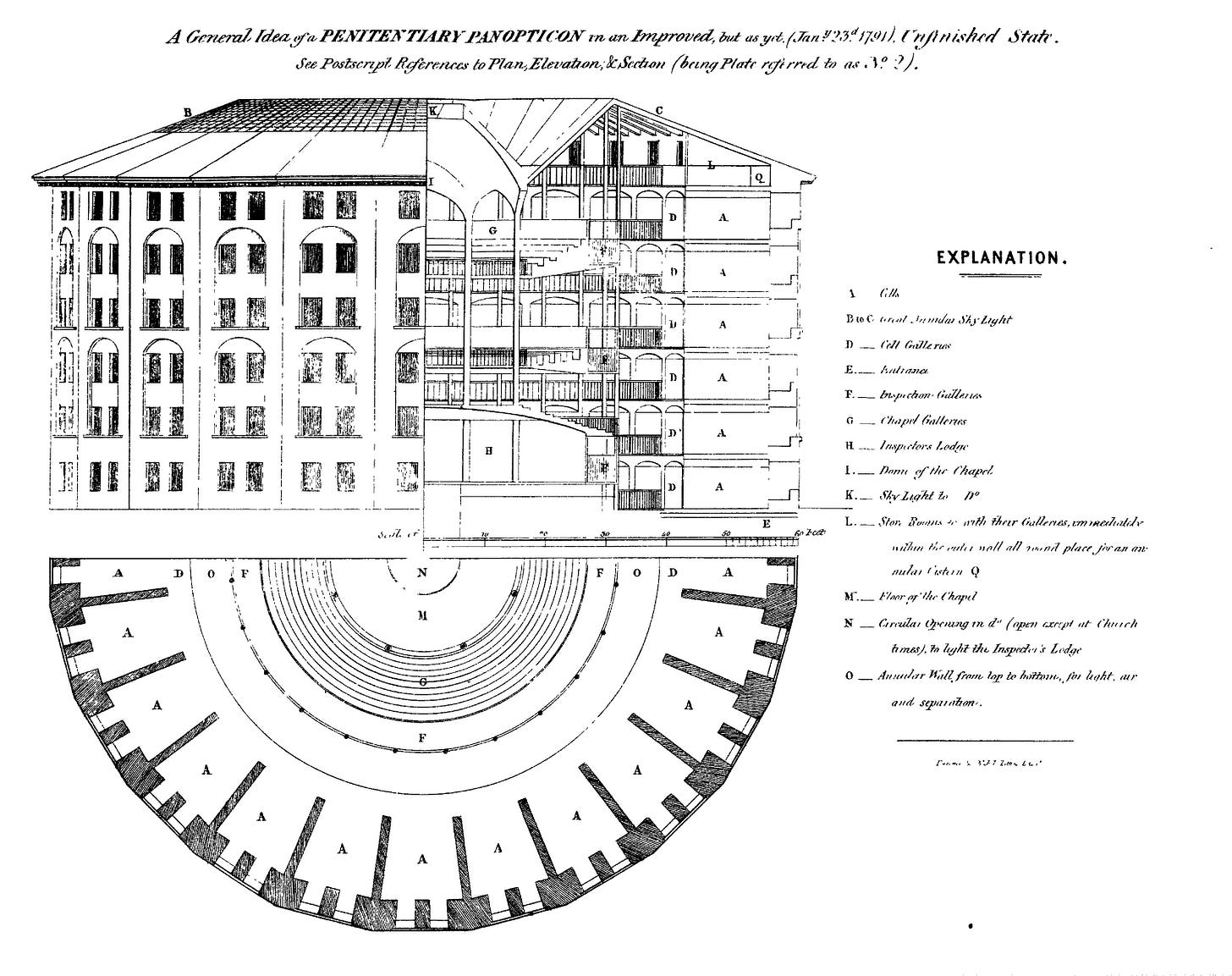

The building is circular.

The apartments of the prisoners occupy the circumference. You may call them, if you please, the cells.

These cells are divided from one another, and the prisoners by that means secluded from all communication with each other, by partitions in the form of radii issuing from the circumference towards the centre, and extending as many feet as shall be thought necessary to form the largest dimension of the cell.

The apartment of the inspector occupies the centre; you may call it if you please the inspector’s lodge.

It will be convenient in most, if not in all cases, to have a vacant space or area all round, between such centre and such circumference. You may call it if you please the intermediate or annular area.

Bentham’s design called for a round building with a single tower in the middle. The tower was surrounded by some large number of cells arranged in a circle, all exposed to the central tower. Subjects would be kept in separate cells, and monitored by a solitary guard in the middle. I used the term “subjects” because Bentham emphasized in his letters how versatile the panopticon could be:

No matter how different, or even opposite the purpose: whether it be that of punishing the incorrigible, guarding the insane, reforming the vicious, confining the suspected, employing the idle, maintaining the helpless, curing the sick, instructing the willing in any branch of industry, or training the rising race in the path of education: in a word, whether it be applied to the purposes of perpetual prisons in the room of death, or prisons for confinement before trial, or penitentiary-houses, or houses of correction, or work-houses, or manufactories, or mad-houses, or hospitals, or schools.

Bentham’s panopticon was designed for the masses, especially for the subjugation of the vulnerable and already oppressed.

With only “a simple idea in Architecture!” Bentham effectively designed a way for the powerful to reform the morals, preserve health, and invigorate industry, among the powerless. And only one monitor would be needed for “obtaining power of mind over mind.”

Morals reformed - health preserved - industry invigorated instruction diffused - public burthens lightened - Economy seated, as it were, upon a rock - the gordian knot of the Poor-Laws are not cut, but untied - all by a simple idea in Architecture!

[…]

A new mode of obtaining power of mind over mind, in a quantity hitherto without example

The panopticon is a diabolically genius idea. Though its simplicity and bluntness hit you over the head like a brick and leave you with a bad hangover. One person can effectively control hundreds, not by monitoring all subjects at every moment, but by convincing them that they could be monitored at any given moment. You never know when the monitor is watching so you behave as though he is always watching.

Visible and Unverifiable

Nearly two centuries later, in his 1975 book Discipline & Punish: The Birth of the Prison, French philosopher Michel Foucault revisited Bentham’s panopticon.

Foucault teased out some of the finer points and clarified the ramifications of the architectural structure that could go beyond the physical manifestation of a prison.

“Hence the major effect of the Panopticon: to induce in the inmate a state of conscious and permanent visibility that assures the automatic functioning of power. […]

To achieve this, it is at once too much and too little that the prisoner should be constantly observed by an inspector: too little, for what matters is that he knows himself to be observed; too much, because he has no need in fact of being so. In view of this, Bentham laid down the principle that power should be visible and unverifiable. Visible: the inmate will constantly have before his eyes the tall outline of the central tower from which he is spied upon. Unverifiable: the inmate must never know whether he is being looked at at any one moment; but he must be sure that he may always be so.

A Clearer View of Everything

2020 has brought about a new age of the panopticon. This one is without walls and is even more “all-seeing” than Bentham’s version.

The New York Times recently released a piece entitled The Secret Company That Might End Privacy As We Know It, detailing a new artificial intelligence company called Clearview AI that’s developed a powerful facial recognition product. Clearview’s facial recognition application is unparalleled in its reach and capacity to recognize the faces of countless people on the street that might be unfortunate enough to cross the path of a device employing it. But Clearview isn’t a best-in-class product because of what the founder Hoan Ton-That says is a “state-of-the-art neural net,” or because of more sophisticated thermal imaging, or because of the implementation of any other particular technological innovation. In fact, Albert Wenger of the venture capital firm a16z wrote on his blog:

“First, it should be clear by now that it has become almost trivial to build a system like this. A lot of open source frameworks and neural networks have been made available that can be trained for face recognition. Clearview AI did not have to come up with some technological breakthrough, they just had to point existing technology at image sources[…].”

Clearview AI is in a class all its own because of their massive database of images to pull from when evaluating a person spotted in the real world. They tout a database of over 3 billion images, each scraped from sites on the open web like Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn, Venmo, and YouTube.

Automated web scraping technology has existed nearly as long as the internet itself. The first internet crawling bot, the World Wide Web Crawler, debuted in the summer of 1993, with the first crawler powered search engine coming that winter.

The usage of web scraping technology is not difficult (Try it for yourself here, here, or here), but the usage of it for the collection of massive amounts of personal information for surveillance is ethically ambiguous at best, morally sinister at worst, and is definitely in direct contradiction to the terms and policies of many popular websites. Twitter’s Developer Agreement and Policy document for example says:

User Protection. Twitter Content, and information derived from Twitter Content, may not be used by, or knowingly displayed, distributed, or otherwise made available to:

1. any public sector entity (or any entities providing services to such entities) for surveillance purposes, including but not limited to:

investigating or tracking Twitter’s users or their Twitter Content; and,

tracking, alerting, or other monitoring of sensitive events (including but not limited to protests, rallies, or community organizing meetings);

2. any public sector entity (or any entities providing services to such entities) whose primary function or mission includes conducting surveillance or gathering intelligence;

Twitter, Facebook, Venmo, LinkedIn, and YouTube have already sent cease and desist letters to Clearview. There’s no indication however that Clearview cares

More important than Clearview’s violation of the wishes of giant tech platforms is their violation of the trust and privacy of millions of Americans. In over three billion instances Clearview has surreptitiously taken the images of unwitting social media and content site users (if you’re reading this, they almost certainly have photos of you) and given them to others to surveil them.

There are now over 600 different law enforcement entities in the United States that have licensed Clearview’s facial recognition product. Everyone from the FBI and the Department of Homeland Security to hundreds of state and local agencies is using Clearview’s tech. It’s had such rapid adoption because it’s simply more powerful than everything else they have. A more common facial recognition tool used by law enforcement might have similar identification technology but certainly has a dramatically smaller database to match from. It might have a database of a few million images: a combination of police collected images from criminal investigations, mugshots, and maybe a state DMV database. It would be limited in size (still massive but not 3 billion images massive) and limited in identification range and flexibility. These government collected photos are often taken straight-on from the front, or directly from the side, and usually feature an individual with a relatively blank expression. Clearview’s ripped photos show people from every imaginable angle and would feature a wide range of expressions; from happy to sad, and everything in between.

Invisible and Verifiable

Clearview’s facial recognition weapon is the panopticon made real and inverted.

Foucault described Bentham’s panopticon as laying down the idea that power, like the monitor within the central tower, should be ‘visible but unverifiable.’

In conjunction with the unregulated ability of companies and governments to track our movements, purchases, thoughts, and desires, Clearview’s product (and the ubiquity of facial recognition policing) represents a new paradigm.

Power will be increasingly invisible but verifiable.

There is no central tower to see and to fear. It’s been digitized, decentralized, and democratized.

And there isn’t a question of whether or not the inspector is paying attention. You are being watched. You are being monitored. You are not anonymous.

Only understanding the issue and having the courage to stand up and speak, even while under the gaze of the panopticon’s eye, will hold power accountable.

R

*(h/t to @benedictevans whose subheading “Building the panopticon” in a recent newsletter lead to my research into the ideas of Bentham/Foucault. Read his essays HERE and subscribe to his awesome newsletter)